Elasticsearch Lessons

I’ve recently spent a fair amount of time working with Elasticsearch and I wanted to take some time to record my thoughts and lessons learned while hopefully avoiding the common best practices article fodder. For anyone working with Elasticsearch I can’t recommend the official docs highly enough.

Elasticsearch is a Search Engine, not a Database

This shouldn’t sound surprising, but misunderstanding this statement and its ramifications caused a lot of headaches on a project. At first glance the usage of Elasticsearch in the project makes sense; the users are looking for fairly small subset of a large collection of documents. This is the kind of thing Elasticsearch excels at, however it ended up being leveraged more as a traditional relational database. This sacrificed a lot of the benefits of the technology and required extra work that was hard to plan for. The search page would initially load with minimal filters in place. Because we didn’t crop results down we ended up attempting to pull all results. This means larger users were hitting Elasticsearch’s 10_000 result size limit which caused a multitude of problems along the data pathway. You can work around limits like this with certain APIs like Scroll, but this has some very real risks around performance and memory usage. I think it would be preferable to really focus on providing only the information the user needs, which probably isn’t thousands of results without some kind of aggregation.

Another issue that cropped up was that many-to-one relationships in the data required a lot of redundancy since that one object had to be stored fully in each associated document. This made some things that are painless in a relational database much more convoluted. As an example, every document in the system was associated with a piece of equipment. When information for that equipment changes you couldn’t just update the equipment table in one spot. Instead you’d have to update every document to include that changed piece of equipment data. We had a piece of information that changed regularly which meant we were constantly updating large swaths of documents. A lot of pain would have been avoided if that equipment data was stored elsewhere and any filtering done on it could be done ahead of time.

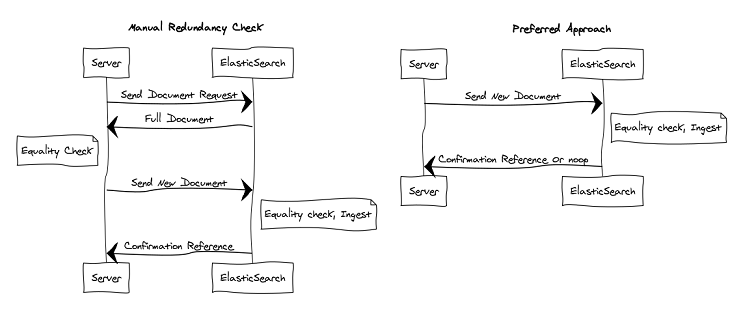

When working with a relational database people are cautious about write operations. For ACID reasons saving changes generally means you’re locking a row or table for the duration of your alteration which is expensive. Due to this there’s a fairly common pattern of making certain that the change you want to store isn’t already present in the database. I saw this idea carried over in our use of Elasticsearch. Any time a document was going to be submitted to Elasticsearch that document would first be retrieved for an equality check on the server. This turned out to have been both redundant and inefficient with our work loads. We doubled our number of network calls and in the case that the update wasn’t needed we were slower than just sending the document to Elasticsearch and letting it return a noop(its default behavior). Since our documents were relatively small and false updates were rare we ended paying large overheads and missing out on the benefit Elasticsearch could provide.

Slow Logs (This is the feature name, not a critique)

Elasticsearch is fast at what it does, but it’s still possible to create queries that are slow if we’re not careful. Waiting on your users to report these speed issues isn’t great. You might even have health metrics on common endpoints but it can be hard to know where that time is being spent if Elasticsearch is only one piece of your backend. Elasticsearch provides built in logging for slow queries that is configurable on a per index basis. Just specify a time threshold and all queries exceeding it will be logged for review. This feature is disabled by default so it’s easy to overlook. The Slow Logs feature provides a great way to have certainty when someone asks you if Elasticsearch is fast enough, and lets you know if you have an issue with a query you’ve written.

It’s About Time

Elasticsearch really shines with temporal data. The farther your use case strays from this the less common Elasticsearch idioms will apply to what you’re doing. One common way to this can surprise people is via the Kibana plugin. Kibana is an excellent dashboard for your Elasticsearch instance that provides a handy searchable exploration tab for examining the data in your instance. It’s easy to forget that this exploration view is time bounded. If the type of document you’re interested in doesn’t have a time-based field it’s impossible to retrieve or view those documents via exploration. This can cause a lot of confusion if you forget about it, but can be bypassed by using the dev tab in Kibana or other tools like Elasticsearch Head that facilitate running queries against the REST endpoints.

I think if I was setting up indexes and mappings in the future I would consider making different indexes for temporal data vs non temporal items. This would let me leverage automatic lifecycle management and other features in the situations where they make sense.